GENE SILBERBERG RECALLS 50+ YEARS AS A JAZZ MUSICIAN

As told to John Ochs, with revisions by Gene Silberberg

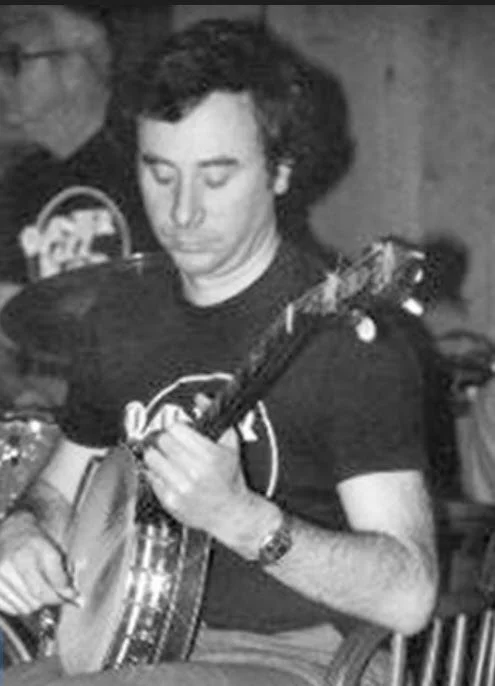

Gene at a 1981 PSTJS concert playing with the Rainier Classic Jazz Band.

I conducted this interview during our summer break. I had been planning to do it for quite a while, but was, I guess, a bit intimidated, since Gene was my professor years ago in two classes while I was pursuing my undergraduate degree in Economics at the UW. Fortunately, the passage of time is the great equalizer, and the interview was not only painless, but enjoyable. —J.O.

Growing up, I was fortunate enough to receive a well-rounded education. My family and most of their friends were secular Jews. Where we lived, if your kid didn’t go to college, the whole neighborhood would find out about it and you’d be so embarrassed you’d have to move out of town.

I attended Stuyvesant High School, which was then an all-boys school in lower Manhattan. Stuyvesant was (and is) a “test to get in” public school which specialized in science and math. At Stuyvesant, the basic elementary skills I learned in my pre-calculus classes introduced me to clever ways of solving problems, which served me well in my future studies and professional career.

My mom was the real musician in the early family. She was a very fine pianist, and when I was nine years old, she enrolled my brother and me in music lessons at the Manhattan School of Music. Because my brother was bigger than me, being two years older, he got the cello and I got a violin. I enjoyed playing classical music in my high school orchestra, but afterward I gave up violin, mainly because I hated the Vivaldi violin concertos my teachers assigned.

I was introduced to 1920s music by a friend whose dad had saved some of his old records. In particular, it was a recording of “Tuck Me to Sleep in My Old Kentucky Home.” The Ain’t No Heaven Seven plays this tune, and I smile to myself each time. I was about 14 years old, and while everyone else my age was listening to popular artists like Elvis, I was enthralled with the music of Fletcher Henderson, Louis Armstrong, and Bix Beiderbecke. Those 6-2-5-1 traditional-jazz chord progressions set up shop in my brain, and my life was never the same.

I graduated from City College in New York in 1960 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Mathematics and Physics. By the time I was a senior, it was obvious to me that I was never going to be either a mathematician or a physicist, so I was considering fields that were “mathematical.” As it happened, in my senior mathematical statistics course I met the one economics major in two sections of the class. He convinced me to apply to Purdue, which was starting a program in “mathematical economics.” We became lifelong friends. So, I earned a Ph.D. in Mathematical Economics at Purdue in 1964 and became an accidental economist. Along the way I met and married my life-long sweetheart, Jane, in 1963.

My first post-doctoral teaching position was at Harpur College in Binghamton, NY. It wasn’t a good fit, so I went to the annual meeting of university economists, in San Francisco in December 1966. After several interviews, I ran into a friend from grad school who was at the University of Washington. He invited me to meet with the delegation from the school’s faculty. As I waited outside the room where he was prepping the group for my introduction, I overheard one of them say, “Oh no, not another one!” I figured that was the end of my chances, but I in fact hit it off with one of the young recruiters and I was hired as an Assistant Professor for the 1967–68 school year.

I bought a tenor banjo when I was still in grad school. Not long afterward, Jim Quirk, my professor at Purdue, contacted me. He had accepted a position at the University of Kansas and asked if I could present a lecture to his Friday class. He also loved traditional jazz and had formed a band in Kansas made up entirely of economists, except it lacked a banjo player. I accepted the offer—more for the jazz than the lecture—and had a great time all weekend playing standard tunes I had never heard before. In particular,I remember learning “Just A Closer Walk With Thee.”

Back at the UW, I mentioned my weekend to my class, and Jake Powel, then an Economics grad student in that class, mentioned he too was interested in trad jazz. Jake was teaching himself cornet, although he was already adept on banjo and guitar. We formed a trio with John Floyd, an Economics Department colleague who played piano. The next year, we met drummer Stephen Joseph, bassist Gary Provonsha, and clarinetist Dick Martin, and we were suddenly getting gigs. The experience of playing around town broadened our acquaintances. I remember a Boeing secretary calling and ordering me to play a jam at one Boeing executive Werner Braun’s house, where I first met clarinetist George Goldsberry.

Gene playing for the PSTJS in the February 19, 2023 version of the ANH7 jazz band when Paul Woltz was subbing for Steve Wright.

In 1970, my colleague John Floyd left for a job at Toronto. Soon afterward, we met Bob Dunn, a terrific pianist who was doing a residency in neurosurgery at the UW. A couple of years later, Bert Barr came to town and assembled the Uptown Lowdown Jazz Band. I joined up with Bert and then dropped out a while, but in 1974, Stephen Joseph came back from NYC and suggested I might still be interested, which I was. We joined the union, played trust-fund gigs hither and yon, and a variety of private gigs. I thought I knew a lot of tunes, but it turned out I knew next to nothing compared with Bert’s vast knowledge of early jazz. I was almost completely ignorant of Jelly Roll Morton’s compositions, and Bert, I think, knew them all.

Steve Joseph’s return to town was a boost for the band. He could get gigs like crazy. Whenever he heard about a new club or cafeteria opening, he’d be down there convincing them they needed a jazz band. We backed up Pat Wright’s Total Experience Chorale group and the choir from the First AME church on Capitol Hill for the Kingdome opening. He even persuaded the Mariners and the Seahawks to hire us. We played between innings for the Mariners and were featured as part of the Seahawks’ pre-game entertainment. The Mariner games were especially memorable, because Steve wrangled free tickets for our kids. We played every week or two, and it was great fun.

The year 1976 was a great year for the Uptown Lowdown. By then, Bert had assembled a book of over 200 arrangements and settled upon relatively stable personnel consisting of himself on cornet; George Goldsberry, clarinet; Ken Wiley, trombone; Bob Dunn, piano; Gary Provonsha, tuba and string bass; Stephen Joseph, drums; Susan Valliant Speer, vocals, and me on tenor banjo. It was a fabulous year, highlighted by the release the band’s first recording (financed by Tom Rippey) and our first trip to the Sacramento Jazz Jubilee, the annual four-day traditional-jazz festival that took place every Memorial Day weekend. The festivals were a revelation. I found people I never met deferring to me because I was a musician, something I’d never experienced as an economist.

In the fall of 1976, the band landed a gig for every Friday and Saturday evening (up from two weekends per month), and I just couldn’t manage that with a wife and three small kids, plus my regular job at the UW and some consulting. So, we parted, but stayed in touch, and I substituted in the band every now and then, and was put on the call list for gigs with the Mariners and Seahawks.

I became a full-time member of the Rainier Jazz Band (RJB) in 1980 when banjoist Barry Durkee suddenly died after collapsing while jogging. Once again, it was Steve Joseph who pleaded my case and convinced leader Bob Pelland to hire me. For most of those years, the band featured Richard (Boots) Houlahan and later, Roy Whipple, cornets; George Goldsberry, clarinet; Al Barrows, trombone; Bob Pelland, piano; Randy Keller, tuba; Stephen Joseph, drums; Ron Rustad, vocal, and me on tenor banjo.

At its peak in the 1980s, the RJB maintained just the right activity level to suit my schedule, with semi-regular gigs at local nightspots along with the occasional private party. We recorded two record albums for Tom Rippey’s Triangle Jazz label and were invited to the Sacramento jazz festival in the early ‘80s.

In the mid-1980s, the rigors of age began to take a toll on some of the band’s musicians, and we stopped receiving invitations to play in Sacramento. In addition, most of Bob Pelland’s time was being taken up by the Grand Dominion Classic Jazz Band, a second band he had co-founded a few years earlier, which was enjoying great success not only at festivals but also as a cruise-ship attraction.

The end of the RJB’s participation in the Sacramento festival meant for the first time in many years I could enjoy Memorial Day at home and attend the Northwest Folklife Festival. I took my banjo along and came across a group of musicians playing old-time fiddle music. They were having so much fun I was inspired to buy a $100 violin at the festival’s fundraising auction. I hadn’t played since high school, and when I practiced, I was appalled to discover that my bowing and intonation were awful.

To remedy the situation, I took violin lessons from Seattle Symphony violinist Martin Friedmann and immersed myself in violin music. Although I was taking classical lessons, I knew I would wind up in fiddle music. I played and recorded fiddle tunes I heard at the open-band contra-dances at the Tractor Tavern and the summer gatherings at Fort Worden in Port Townsend. I simultaneously started recording and transcribing fiddle tunes, gradually compiling transcriptions of 569 old southern tunes that I published in 2000 and later with another 150 tunes in 2006 under the title The Complete Fiddle Tunes I Either Did or Did Not Learn at the Tractor Tavern. In addition, I formed and played lead fiddle with the ChordWood String Band, a five-piece acoustic ensemble that played old-time dance music.

In the mid-90s, I invited myself into Al Rustad’s Cornucopia Concert Band. I told him he needed a banjo player. I loved the Americana that band did, and I also plunked along on some of the German marches. I also still play jazz as a member of the Ain’t No Heaven Seven band, a job I inherited when the band’s first banjoist, Dr. Karl May, died in 2004. Also, for the past 20 years, I’ve been jamming on fiddle with the bluegrass crowd, a transition that keeps my creative juices flowing.

I retired from teaching Economics at the University of Washington in 2008, but here I am, 85 years old, still playing music and enjoying every minute of it! I’d do it all over again.